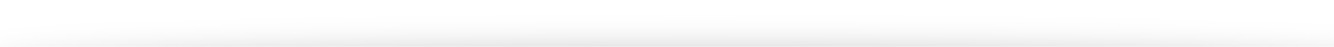

Recognising the Subtle Moments That Tell Us It’s ‘Not OK’

When it comes to intimate partner violence, the early signs can be hard to miss. Sure, if a victim has been physically abused or thrown out of their home by their partner, it is more obvious. But detecting the first signs of abuse is not always straightforward, especially when bad behaviour is normalised. This was the task assigned to strategic communications and design agency, INTENT, when they partnered with women's support organisation Optimism Place for their latest campaign. Recognising the nuanced nature of the job at hand - making subtle signs impossible to ignore - INTENT utilised its time and resources to deliver on this purposeful brief.

Informed by real data and insights from a local domestic abuse training course, the INTENT team ensured they were as clued up on the subject as possible in order to avoid triggering those in need. Determined to avoid sensationalism of any kind, Ben Hagon, president of the agency, explains how the agency worked closely with Optimism Place to craft a community activation with grassroots visibility that would evoke real behaviour change and tangible impact. Here, he speaks to LBB’s April Summers about this very important – and impactful – work.

LBB> When you first engaged with Optimism Place, what were the key insight gaps or misconceptions around intimate partner violence that shaped your strategic direction?

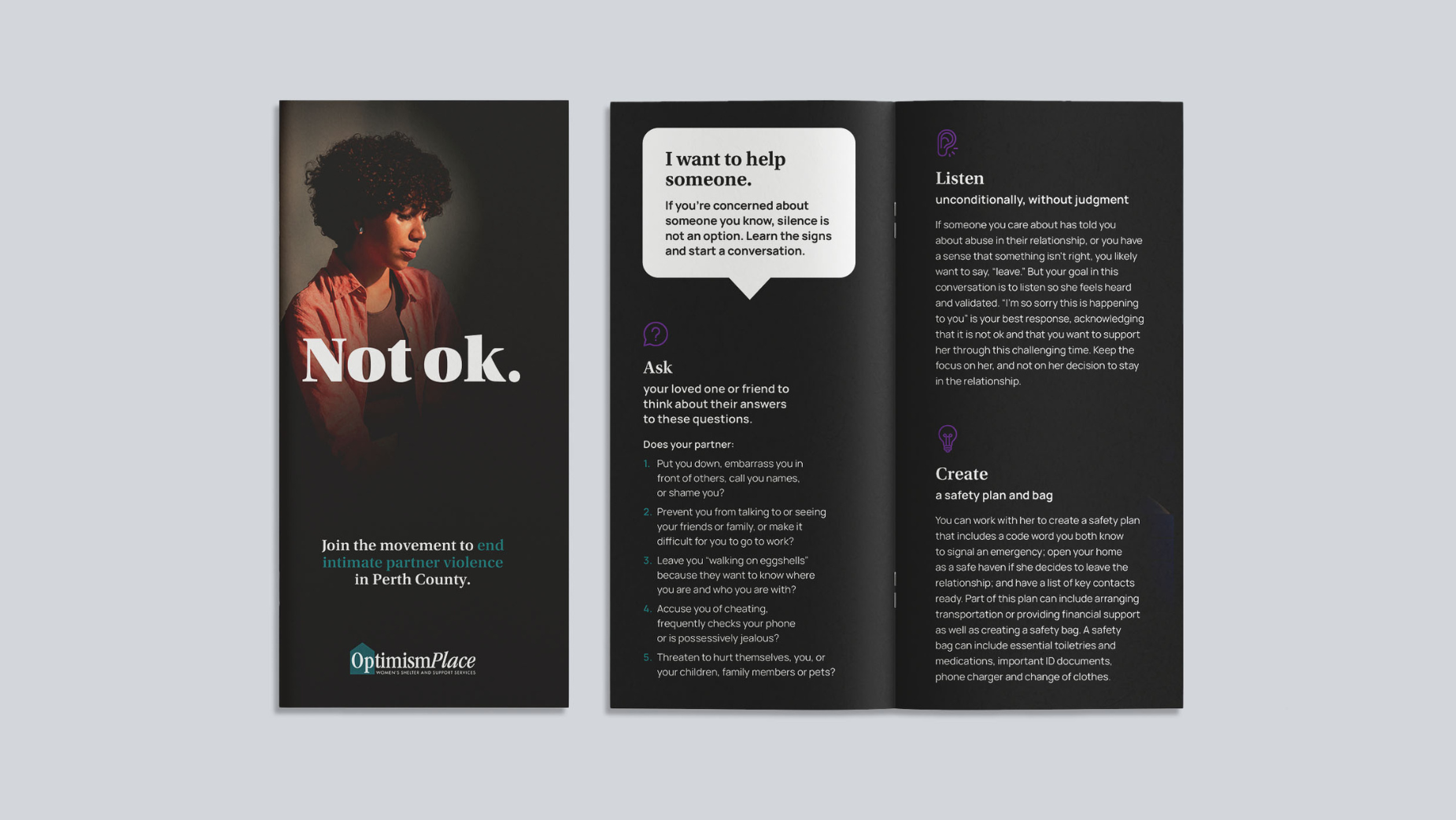

Ben> One of the main gaps in advertising in this space, as we saw it, was that most intimate partner violence campaigns focus on the late stages of abuse. Whether it be when a person has been kicked out and made homeless, or perhaps when there are physical signs of abuse, all sorts of different things. For us, that focus was too late, by that stage women can be at far greater risk. It's maybe more effective when you're trying to raise money – but we're not trying to raise money here. We were focused on helping people understand the warning signs, in order to help the client intervene sooner, which leads to much more positive outcomes than rescuing a person when they're already deeply in trouble.

We didn’t come with preconceived ideas, this focus was a result of our consulting work with the client and their stakeholders. This stemmed from the idea of helping people in a rural community who assume that there are very little to no issues with this topic in their community understand how to keep an eye out. So it made more sense to focus on raising awareness of the signs of coercion and control, rather than physical, mental and sexual abuse.

LBB> And if this campaign isn’t in aid of raising money per se, what was the most important behavioural shift that Intent hoped to spark?

Ben> Women getting support. The real behavioural shift was for people in the community and the county to understand that there is a place for them, and to understand their course of action. And if folks might know someone who could be in trouble and have concerns, they can get information and help from an organisation in the community.

LBB> Tell us a bit more about the kind of local data or lived experiences that formed your understanding of how early these kinds of coercive control methods take hold?

Ben> What really stood out was the amount of calls that were placed to emergency services. There are over 600 police calls related to GBV/IPV in Perth County every year – this is particularly shocking because this is a very small rural community.

Optimism Place has been in the community for a long time and told us that not only was there a problem, but there was a lack of awareness of the problem, which is what they wanted to shift.

LBB> What did you learn in the process about how these communities typically misunderstand issues and pass it off as just ‘typical’ relational problems?

Ben> Well, we learned that the community is primarily an agricultural community, so people live very far from one another in terms of distance. It’s not like in a city where your next door neighbour might need help, and they are right there. In a rural community, they could be acres away. So that was one element.

The other element is that there are significant populations of very specific religious communities, and that can make things additionally complicated because of how close-knit those communities are. That’s not to say there's a greater problem amongst those communities, but things happen.

In addition to the geographical and cultural element of the issues in Perth County, there was also the fact that, if you're a woman who's being abused, your entire family will likely be working on the family farm, as well as your partner’s family and maybe your friends will be related to the farm somehow too. Communities within communities, within communities, very different to other social contexts. This means these people require real support in terms of extraction and ongoing support.

What’s really interesting about Optimism Place is that they're not just a shelter, they provide a range of services. So if you're a woman that has noticed some of these signs of coercion and control, there are programmes that you can engage in to get help and navigate the situation. You don't have to leave, you don't have to go into shelter to get support — that was really important for the campaign as well.

LBB> Can you talk a bit about the creative spark behind the campaign? The moment where you knew that it needed to be more about naming the behaviours instead of dramatising them.

Ben> I think the first creative spark was this idea of signs. We began conceptualising the ideas of ‘signs’ and stop signs specifically. As I said, the strategy was to focus on coercion and control, not just the physical manifestations or symptoms of abuse. As we looked at the community, and observed this mixture of agricultural or traditional manufacturing, we realised it's a very pragmatic community. As a result, the final campaign is a mixture of two pieces of pragmatism.

The first is to show real life scenarios, and the second, is to use real vernacular that people say all the time. “That’s not OK” is a common phrase that people say. We wanted to really reflect a pragmatic approach.

We ended up with over 15 different scenarios that we're running with that are designed to initiate a response like, “Oh, I know somebody whose husband says that...” We wanted to make the point that in isolation, maybe some of these things are typical, relational behaviour, like you said, but when you start compounding more than one of the symptoms, that's when we really have a problem. For example, “can I look at your phone?” Not great, but maybe just a behavioural response. Then, “can I look at your phone? And I don't want you going out with those people.” Now we have the beginnings of a problem.

We wanted to make things really clear and striking for folks, and have the scenarios look familiar which we show them watching Netflix or playing hockey or whatever it might be. We wanted that familiarity to make people feel connected to the campaign locally.

LBB> I see, so the team was intentionally avoiding sensationalism and instead presented relatable, everyday moments. How did you craft a tone to match that approach, which was both unflinching and safe for audiences living through those situations? What were the non-negotiables from a safety standpoint?

Ben> With the expertise of our clients. We worked very closely with our clients to make sure that the language is appropriate, and wasn't going to trigger anybody or be sensationalist. And then the other really interesting thing that we did is that our strategist and our art director participated in a training course that actually focused on these issues. This meant that when they were drafting the messaging and crafting the creative, it was informed by the training they had received.

LBB> You were really covering all bases then! So how did survivor insights or shape the campaign execution, especially the decision to avoid a digital-only approach?

Ben> Trauma informed was the key, as well as sort of the evidence based framework on what to do in the situation. By learning what to do in the situation, that informed the situations themselves and the creative came from that.

LBB> I'm curious about what you might have also uncovered about the cultural norms or everyday reasons that allow these types of behaviours to be dismissed?

Ben> It’s a general normalisation of these behaviours. If we truly ask ourselves, we all know somebody who's had a bad experience, or is having this experience and unfortunately we become familiar with some of these activities and behaviours. With this campaign, what we really wanted to say is if you hear about these instances, offer help. The normalisation of the behaviour that we really wanted to highlight and let people know, it’s not OK when this happens, and please keep an eye on it because you can help somebody avoid a very difficult situation if you do notice these behaviours.

LBB> Why was it essential for this to be in a physical, everyday space, in terms of out of home, workplaces and healthcare settings, rather than relying on digital or tech? Was their strategy behind that?

Ben> Very much. What we know from the data and from our clients' experiences of many rural and agricultural communities, women aren't always allowed phones, and if they are allowed phones, they are monitored. For this reason we wanted to be very careful, almost covert with our media decisions.

We also held a workshop and had stakeholders in the room who had been in similar situations, and they said there's absolutely no way they’d have been allowed to phone. And if they were allowed a phone, their partner would check it all the time. So we couldn't really use phone or computer based marketing communications.

We're trying to create community awareness and the way to do that in Stratford and Perth County is to use the community so this means workplaces, retail, hockey arenas, community centres, libraries, doctors offices. We know these folks go to all these places and we were very selective about the placement of this campaign.

We also chose traditional media as well. There were concerns with the way that the Meta platforms and others are going that they would throttle and censor our campaigns anyway, because of the political and decision making of those organisations, so we did shy away from those as well, for that reason too, because we just didn't have any faith that they would let us run the campaign properly.

LBB> Since this is about raising awareness, but also about helping by intervening early, it's not necessarily crisis focused. So how do you measure a campaign like ‘earlier recognition’? What does success look like?

Ben> After being live for two weeks [at the time of interview], four large local organisations have already got in touch with Optimism Place to offer their support and request information. We have had 16 businesses sign up to be partners for the campaign. We've had over 20 information requests directly through the website, and we've already had tens of thousands of hits on that website — and that’s a lot when you consider how remote Perth County is.

It’s really working, and the more businesses and organisations that get in touch, the more materials are out there in the world, and hopefully this means more calls. The ultimate measure is calls. We get an update from the executive director at Optimism Place every day and she's just so happy with all of the attention it's getting.

LBB> That's incredible, what amazing feedback! So do you see ‘Not OK’ evolving into an ongoing platform? What opportunities do you think exist to deepen that cultural footprint over time?

Ben> It already is starting to evolve. We're talking in January about a new campaign.

There is also a kind of underground campaign that we've been creating — but I can’t say too much about that just yet. But we are certainly starting to evolve the campaign and will keep the momentum going into the New Year.

If you or someone you know may be in need of support, don't stay silent. Instead, please visit the Optimism Place website here.