Nils Leonard Says Ads Don’t Need More Polish – They Need “the Thing”

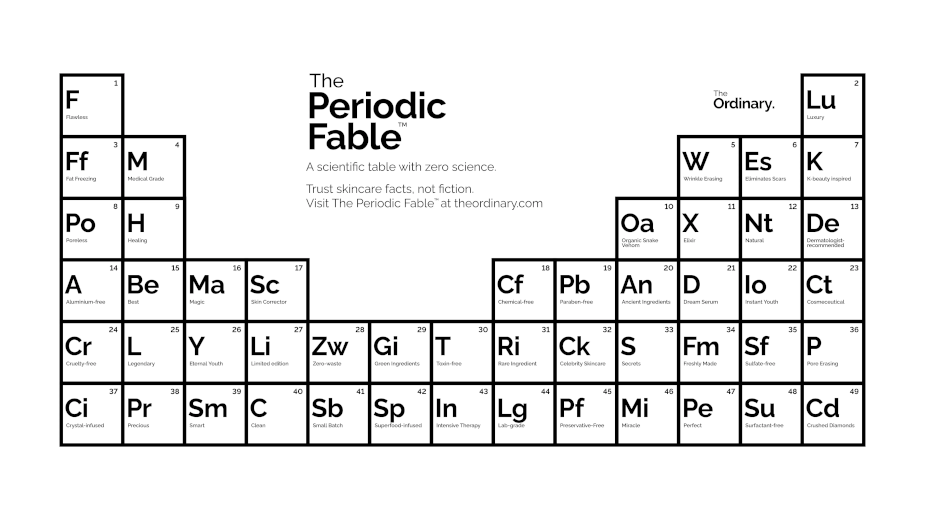

“We realised, for maybe 50, maybe even more years, the beauty industry has just been making up words,” said Nils Leonard, opening his Most Contagious keynote with the kind of blunt clarity that Uncommon has built its reputation on. Working with skincare brand The Ordinary, the studio he leads creatively has been tearing down clichés. From “age-defying” promises to what he gleefully mocked as “elixirs” – “What are you, Merlin?” – the category’s pseudo-scientific vocabulary has long relied on fantasy to sell skincare. The studio’s work for The Ordinary over the past couple of years, he argued, cuts through because it isn’t trying to polish the fiction. It exposes it. And in doing so, it reveals what he considers the only thing that really matters in advertising today: “the thing” – the core idea with enough truth and depth to travel on its own.

If the industry thrived on smoothing over reality, Nils said the job of modern creativity was the opposite: surface the cracks. He insisted that the strange, awkward or “ugly” elements inside a story weren’t liabilities – they were the parts people remembered and repeated. The Ordinary’s work, especially ‘The Periodic Fable’, embraced this wholeheartedly. By cataloguing the bizarre, contradictory vocabulary the industry relied on, it offered audiences the shock of recognition. “Never throw away the ugly details,” said Nils. “They're kind of the thing.” And in a world where opinions are formed in social feeds, highlighting the bullshit with a work of design is the act that sets off a chain reaction. “People basically find a way to tell your story for you.”

From there, he argued that the instinct to perfect, polish and close every loop was misplaced. Perfection created dead space, it gave audiences nothing to do. “Don't be tempted to tie a bow on it,” he said, recalling advice that has shaped much of Uncommon’s approach. Instead of completing the message, he advocated for ideas that deliberately left room for participation. “Find a way for other people to come in and have the conversation on your behalf.” ‘The Periodic Fable’ worked because it wasn’t a final statement, but an open system. People gravitated towards whatever ‘element’ spoke to their own experience and shared those discoveries because the format invited them to.

The real measure of creative potency, Nils argued, was what happened when you stepped back. The Ordinary work showed that a strong idea didn’t need brand cues, explanation or aesthetic smoothing to spread – it simply needed substance. Audiences chose their favourite elements from ‘The Periodic Fable’, shared the ones that exposed something they’d personally fallen for, and in doing so carried the story further than any paid plan could. They “found their own favourite one… the one that they'd been conned by,” he said. When people recognised themselves in an idea, they propelled it.

What gave The Ordinary’s work its cultural weight, Nils said, was the depth beneath it. It was built on real interrogation of the industry’s language and claims. “We went and did our research, tracked it all down,” he said, describing how every term in ‘The Periodic Fable’ was sourced from decades of beauty jargon. That rigour allowed the brand to speak softly but land powerfully. When an idea was grounded in genuine investigation, audiences felt it. “The work is the thing,” he said – and polish, by implication, is just decoration.

He then challenged the creative complacency baked into social platforms. “You know ‘social media best practice’? The reason that exists is that they assume that most of what we're going to make is kind of crap.” Those rules – brand in the first seconds, compressed edits, forced emotional uplift at the end – were scaffolding for weak ideas. The Ordinary’s film, which was a part of the campaign (but not the thing itself) ignored all of them: a slow, strange, 60-second piece with no early branding, yet it travelled anyway. Its success reinforced Nils’ point that when the creative idea is strong enough, it doesn’t need the algorithm's stabilisers. Great ideas withstand – and even break – the rules designed for mediocre ones.

As automation accelerates and feeds fill with machine-made content, Nils said human originality has become more valuable, not less. Decision-making might increasingly be shaped by algorithms, but what still cut through was work that felt unmistakably authored. “Uncommon's view of the world is that what we offer is the last great scarcity,” he said – a finite resource in an age of infinite output. The Ordinary embodied this through radical transparency and cultural sharpness. When everything started to look the same, perspective became the only meaningful point of difference.

He shifted to a broader ambition: brands should behave like participants in culture, not commentators on it. He pointed to Red Bull as proof – a brand remembered for acts, not campaigns. “Do you remember when Red Bull made a drink,” he joked. “What are they doing diving out of space.” The drink feels like a small detail compared to how that brand behaves in culture. The Ordinary’s open-source white papers and truth archive reflected the same ambition: moves designed to reshape its category, not simply advertise within it. “What if the brand was constantly in culture?” Nils asked. “What if it found a way to change things, not just speak up about them?” In other words, what if the brand consistently acted around “the thing” rather than polishing the surface?

But none of this work, he said, was possible without the right people around the table. The biggest barriers to transformative ideas aren’t budgets or timelines but fear and small ambition. “Often, you realise when you go to make work like this… [clients and partners] are less ambitious than you. They're more scared. They don't care. They become a blocker.” The Ordinary’s marketing team cleared that hurdle by believing in transparency and backing it without hesitation. True creative progress depended on partners willing to take risks alongside you.

Nils ended on something closer to a plea. The greatest threat to creative ambition, he said, wasn’t the algorithm or the industry’s fictions – it was cynicism. The belief that brands couldn’t change anything, that audiences didn’t care, that bold ideas wouldn’t land. “Give yourself permission to imagine your brand might matter. And imagine your work might matter,” he said. “If you could take anything from my wanging on… it would be the removal of cynicism.” In his view, hope isn’t naïve – it is the creative tool. And, in a world obsessed with polish, believing you can actually change something is the only real place to begin.